Wholesale Economics: How Generic Drug Distribution and Pricing Really Work

Nov, 13 2025

Nov, 13 2025

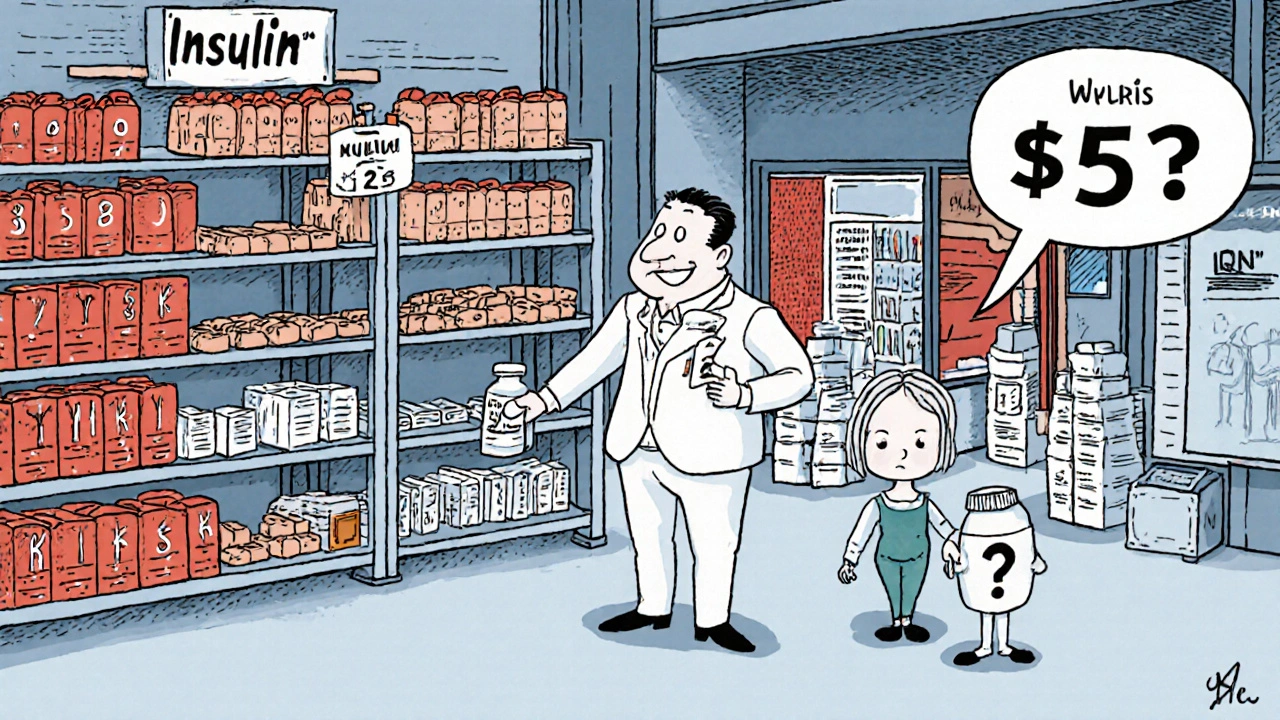

When you pick up a prescription for a generic pill at your local pharmacy, you probably don’t think about how it got there. But behind that $5 bottle of lisinopril or metformin is a complex, high-stakes economic system that moves billions of dollars every year-and where the real profits aren’t where most people expect them to be.

The Three-Tier System No One Talks About

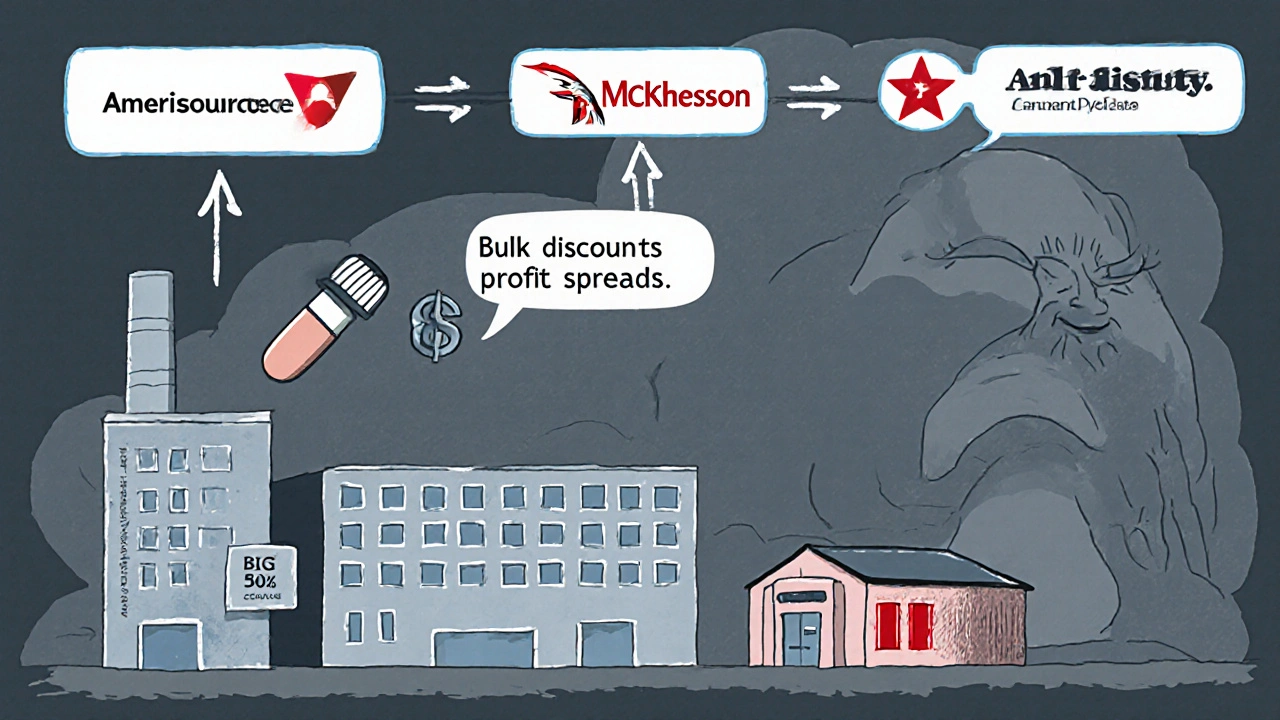

The path from a drug manufacturer to your medicine cabinet isn’t direct. It goes through three layers: manufacturers, wholesalers, and pharmacies. This structure was formalized in 1987 by the Prescription Drug Marketing Act, but its economic logic hasn’t changed much since. The big players? AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson. Together, they control about 85% of the U.S. generic drug wholesale market. That kind of concentration means they hold serious power-over manufacturers, over pharmacies, and over prices.Why Generics Are the Hidden Goldmine

You’d think branded drugs make the most money. After all, they cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars. But in the wholesale world, generics are the real profit engines. In 2009, generics made up only 9% of the total revenue for the Big Three wholesalers-but they delivered 56% of their gross profits. That’s not a typo. Wholesalers made eleven times more profit per unit on generic drugs than on branded ones: $32 versus $3. Pharmacies made nearly the same: $32 per generic unit versus $3 per branded one. Why? Because generic manufacturers are desperate to get their products onto pharmacy shelves. With no patent protection, they compete on price. To win contracts with big wholesalers, they slash prices aggressively. That leaves wholesalers with huge spreads between what they pay and what they charge pharmacies. It’s not about volume alone-it’s about pricing power.How Wholesalers Actually Make Money

Wholesalers don’t make money by marking up prices wildly. Their net profit margin is shockingly thin-just 0.5%. That’s because they handle massive volumes. A single truckload can carry hundreds of thousands of pills. Profit comes from squeezing every penny out of each transaction through volume discounts, rebates, and logistics efficiency. They use tiered pricing to push pharmacies into buying more. If you order under 100 units, you pay $10 per pill. Order over 100, and it drops to $8. Go over 500, and it’s $7. These aren’t random numbers. They’re engineered to lock in bulk buyers. Shipping costs are baked in too. If a pill costs $10 to make and $2 to ship, the wholesaler won’t sell it for $10. They’ll charge $12-because they can’t afford to lose money on delivery.Cost-Plus vs. Market-Based Pricing: The Two Real Strategies

Wholesalers don’t just guess at prices. They use two main models:- Cost-plus pricing: Add a fixed percentage (usually 20-50%) to the total cost of the drug, including manufacturing, shipping, storage, and handling. Simple. Predictable. But risky if competitors undercut you.

- Market-based pricing: Watch what others charge and match or beat them. This keeps you competitive but can turn into a race to the bottom-especially in crowded generic markets.

Who Makes the Real Money? The Numbers Don’t Lie

Let’s break it down:| Entity | Gross Margin on Branded Drugs | Gross Margin on Generic Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | 76.3% | 49.8% |

| Wholesaler | Low (single digits) | High (up to 40%+ on gross profit) |

| Pharmacy | 25-30% | 42.7% |

Why This System Is Under Pressure

The generic drug market was in a deflationary spiral from 2021 to 2022. Prices kept dropping as more manufacturers entered the space. But in 2023, everything changed. Shortages of key generic drugs-like those used in ICU care or for chronic conditions-started appearing. When supply drops and demand stays high, prices jump. Wholesalers, sitting on inventory, suddenly had leverage. Some prices doubled or tripled overnight. The Commonwealth Fund says this isn’t just bad luck. It’s a feature of the system. Wholesalers have influence over which drugs get prioritized, which get delayed, and which get labeled “in shortage.” That gives them power to manipulate the market-not by breaking rules, but by playing the game better than anyone else.What Could Change?

Experts like Dr. Neeraj Sood from the USC Schaeffer Center argue that the current system needs more competition. Right now, the Big Three control almost everything. Smaller wholesalers can’t compete on scale. New entrants struggle to get contracts. If more players entered the market, prices might fall. But consolidation isn’t slowing down. Regulators are watching. The government has started asking questions about how list prices are set, how rebates are hidden, and whether wholesalers are contributing to drug shortages. But meaningful reform? That’s still years away.What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you’re paying for a system designed to maximize profits for intermediaries, not to minimize your costs. A $5 generic pill doesn’t cost $5 to produce. It might cost $0.20. But the path it takes to get to you adds layers of markup-and most of that markup goes to wholesalers and pharmacies, not the makers. If you’re a small pharmacy owner, you’re stuck in the middle. You need generics to stay profitable, but you’re at the mercy of wholesalers who control supply and pricing. If you don’t buy in bulk, you pay more. If you do, you tie up cash in inventory that might sit for months. And if you’re a policymaker? The data is clear: the current model isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as intended-for the people who run it.Why are generic drugs cheaper at some pharmacies than others?

It’s not about the drug-it’s about the supply chain. Pharmacies that buy in bulk directly from wholesalers get better pricing. Chains like Walmart and Costco use their buying power to negotiate lower wholesale rates, then pass savings to customers. Independent pharmacies often pay higher prices because they order smaller quantities. Some also get rebates from PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers), which can lower the final price even further.

Do wholesalers cause drug shortages?

They don’t cause shortages directly, but they influence them. Wholesalers decide which manufacturers to prioritize, which orders to fulfill first, and which drugs to stock. If a generic drug becomes profitable, they’ll stock more. If it’s cheap and plentiful, they might stop carrying it. When a shortage hits, they’re often the first to raise prices-and the last to increase supply. Their inventory decisions directly affect availability.

Can the government fix generic drug pricing?

It can try, but it’s complicated. The government can’t directly control wholesale prices because they’re private business decisions. However, it can increase transparency, require public reporting of prices, and encourage competition by supporting new manufacturers or breaking up monopolies. Medicare and Medicaid already negotiate prices, but those deals don’t always reach private pharmacies. Real change would require restructuring the entire distribution chain.

Why don’t manufacturers just sell directly to pharmacies?

They could, but it’s not practical. Wholesalers handle logistics, storage, billing, and delivery for thousands of pharmacies across the country. A small manufacturer might make 100,000 pills a month. Delivering them to 5,000 pharmacies individually? That’s impossible without a massive infrastructure. Wholesalers act as the middleman that makes scale possible-even if they take a big cut.

Is there a better way to distribute generic drugs?

Yes-but it’s not simple. Some experts suggest regional cooperatives where pharmacies pool orders to get bulk discounts. Others propose direct manufacturer-to-pharmacy models for high-volume generics. A few states are experimenting with public wholesalers to cut out private intermediaries. But all of these face resistance from the current system. Change requires not just policy, but a complete overhaul of how the industry operates.

Peter Aultman

November 14, 2025 AT 15:29Man i never thought about how much profit wholesalers make on generics

Sean Hwang

November 15, 2025 AT 10:24yeah the system is wild. i work in a small pharmacy and we get crushed by the bulk buyers. we pay more, get less stock, and still have to charge patients the same. its not fair.

Barry Sanders

November 15, 2025 AT 19:19This is why capitalism is a scam. Wholesalers are the ultimate parasites.

Chris Ashley

November 16, 2025 AT 23:14so wait you're telling me my $5 pill cost 20 cents to make?? that's insane. who's really getting rich here??

Scarlett Walker

November 18, 2025 AT 14:22it’s not just the wholesalers - pharmacies are stuck in the middle too. i’ve seen owners cry over their inventory sitting for months because they couldn’t afford to move it.

Brittany C

November 19, 2025 AT 04:11the tiered pricing mechanism is a classic example of behavioral economics applied to pharmaceutical logistics. it exploits loss aversion and anchoring effects to induce bulk purchasing behavior among independent pharmacies.

Jane Johnson

November 20, 2025 AT 09:12Actually, the real issue is that patients are being misled into thinking generics are cheap because they’re affordable. The system is designed to obscure the true cost structure so consumers never question it.

Sean Evans

November 21, 2025 AT 11:58lol the system is working PERFECTLY for them 😂💸. Meanwhile, grandma’s insulin costs $500 because some dude in a suit decided to ‘prioritize’ another drug. #capitalism

kshitij pandey

November 22, 2025 AT 10:45in india we have a different model - community pharmacies and state-run distributors keep prices low. maybe america needs to think beyond profit. people need medicine, not spreadsheets.

Anjan Patel

November 22, 2025 AT 17:11WHEN WILL WE STOP ALLOWING CORPORATIONS TO CONTROL LIFE-SAVING DRUGS?! THIS ISN'T JUST ECONOMICS - THIS IS CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE!!

Brian Bell

November 23, 2025 AT 22:56the part about how wholesalers decide who gets stock during shortages? that's wild. they're basically playing god with people's lives.

Hrudananda Rath

November 25, 2025 AT 13:17It is lamentable that the United States has institutionalized a distributive mechanism predicated upon extractive rent-seeking behavior by oligopolistic intermediaries, thereby subordinating public health to corporate profitability - a moral abomination of the highest order.

Peter Aultman

November 26, 2025 AT 10:59you know what? i just checked my last prescription. $5. probably made for 15 cents. i’m just glad i can afford it. but yeah… someone’s making bank.