Understanding Adverse Event Rates: Percentages and Relative Risk in Clinical Trials

Jan, 7 2026

Jan, 7 2026

EAIR Calculator: Exposure-Adjusted Incidence Rate Calculator

Calculate Your EAIR

Exposure-Adjusted Incidence Rate (EAIR)

Per 100 Patient-YearsWhy this matters: The FDA requires EAIR for accurate safety reporting because simple percentages misrepresent risk when treatment durations vary. A 45% event rate might seem scary, but if patients were exposed for 3 years versus 6 months, the real risk is much lower.

EAIR accounts for actual exposure time, allowing fair comparisons between trials of different durations. This helps patients and doctors understand true safety profiles.

When you hear that a new drug causes headaches in 15% of patients, it sounds simple. But what if one group took the drug for 3 months and another took it for 2 years? That 15% doesn’t tell the whole story. Adverse event rates aren’t just about how many people got sick-they’re about how long they were exposed, how often events happened, and whether the data accounts for real-world complexity. The FDA is shifting away from outdated methods, and if you’re reading clinical trial results, you need to know why.

Why Simple Percentages Mislead

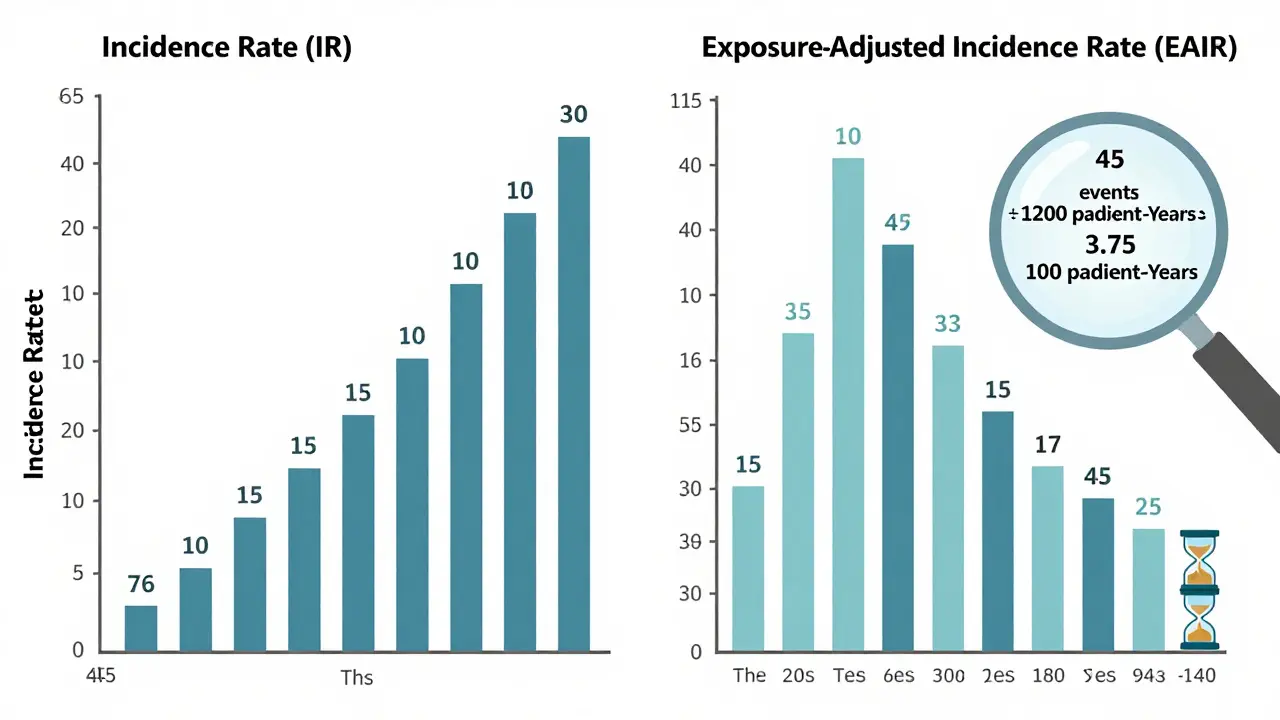

For decades, the go-to way to report adverse events was the Incidence Rate (IR): divide the number of people who had an event by the total number of people in the study. If 30 out of 200 patients got nausea, you say 15%. Easy. But here’s the problem: it ignores time. Imagine two groups in a diabetes drug trial. Group A gets the drug for 6 months. Group B stays on it for 3 years. In Group A, 10 people report nausea. In Group B, 45 people do. The IR says Group B has a 45% nausea rate versus Group A’s 10%. That looks scary. But if you dig deeper, Group B had 18 times more exposure time. That 45% isn’t a higher risk-it’s just more time for nausea to show up. The FDA noticed this. In 2023, they asked a biotech company to resubmit safety data using a different method because the original IR made a drug look riskier than it was. That’s not a technicality-it’s a safety issue. Misleading numbers can scare patients, delay approvals, or even block useful treatments.What Is Exposure-Adjusted Incidence Rate (EAIR)?

The solution? Exposure-adjusted incidence rate, or EAIR. Instead of counting people, EAIR counts patient-years. One patient taking a drug for one year = one patient-year. Ten patients taking it for six months = five patient-years. The formula is simple: total number of adverse events divided by total patient-years of exposure. Then you scale it to per 100 patient-years for readability. If 45 nausea events happened over 1,200 patient-years, the EAIR is 3.75 per 100 patient-years. Now you can compare that to another drug with 5.2 per 100 patient-years-even if one trial lasted 1 year and the other lasted 5. EAIR doesn’t just fix time issues. It also handles recurrence. If one patient gets nausea 3 times in 2 years, EAIR counts all three events. That’s important because some side effects aren’t one-offs-they’re ongoing. A single person having 5 migraines on a drug tells you more than 5 different people having one each. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance on exposure-adjusted analysis says EAIR should be standard for serious adverse events. CDISC, the group that sets data standards for clinical trials, now requires EAIR reporting in oncology trials starting in 2023. Companies like MSD found that switching to EAIR uncovered safety signals they’d missed for years-especially in chronic disease trials where patients stay on drugs for decades.When EIR Works-and When It Doesn’t

There’s another method called Event Incidence Rate (EIR), which also uses patient-years. It’s often confused with EAIR, but there’s a key difference: EIR counts events per patient-year, but doesn’t always adjust for multiple events per person. In practice, many use EIR and EAIR interchangeably, but regulators are starting to distinguish them. EIR is great for recurrent events like rashes, diarrhea, or coughing fits. But if you’re studying something like death or hospitalization, counting multiple events per person doesn’t make sense. One person can only die once. That’s where EAIR’s structure-counting events while adjusting for exposure-fits better. The real trouble with EIR comes when patients drop out early. If someone stops the drug after 2 weeks because of side effects, their short exposure still counts in the denominator. But if you don’t account for why they left, you might overestimate risk. EAIR handles this better by tracking exact start and end dates of treatment, including interruptions. A 2023 PhUSE survey found that 23% of early EAIR calculations had errors because teams used the wrong dates or ignored treatment breaks. That’s why standardized tools like the PhUSE SAS macros-downloaded over 1,800 times-are becoming essential. Without them, even experienced statisticians make mistakes.Relative Risk and Why It’s Not Enough

You might see phrases like “the drug doubles the risk of liver injury.” That’s relative risk-or more precisely, incidence rate ratio (IRR). It’s the ratio of the event rate in the treatment group versus the control group. If 5 per 100 patient-years get liver injury on the drug, and 2.5 on placebo, the IRR is 2.0. But here’s the trap: relative risk looks dramatic, but absolute risk tells you what matters. A 2x increase sounds scary. But if the baseline risk is 0.1% and the drug raises it to 0.2%, you’re talking about one extra case per 1,000 people. That’s very different from a baseline of 10% jumping to 20%. The FDA now requires both absolute and relative measures in safety summaries. They want you to see the full picture: the rate per 100 patient-years and the ratio compared to placebo. One without the other is incomplete.Competing Risks and Why Kaplan-Meier Fails

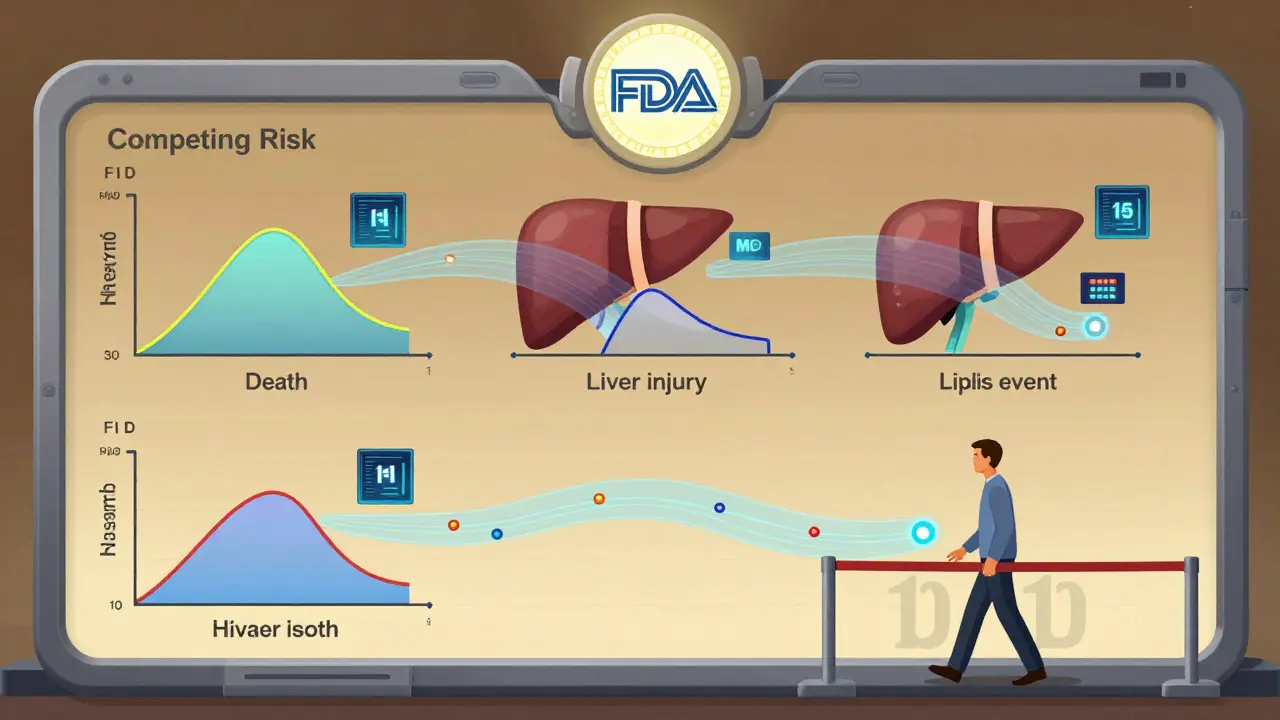

Here’s a hidden problem: patients die. And if they die, they can’t have another adverse event. That’s called a competing risk. In cancer trials, for example, many patients die from the disease before they ever get a rare heart side effect. If you use the old Kaplan-Meier method to estimate how long until a side effect happens, you’ll underestimate the true risk. Why? Because it treats death as if it’s just a lost observation-not a reason the patient stopped being at risk for the event. A 2025 study in Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics showed that traditional methods underestimated adverse event rates by up to 22% in trials where death rates exceeded 15%. The fix? Cumulative hazard ratio estimation. It breaks down the risk into separate pathways: death, heart event, kidney event. Each has its own hazard function. You don’t pretend death didn’t happen-you model it as a competing force. This isn’t theoretical. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is now testing machine learning models that use this approach to detect safety signals earlier. Early results show a 38% improvement in catching hidden risks.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient reading a drug label: look for numbers like “per 100 patient-years,” not just percentages. Ask: “How long were people on this drug?” If it’s not stated, the data might be misleading. If you’re a clinician reviewing trial results: don’t trust IR alone. Compare EAIR values between arms. Check if the study adjusted for treatment interruptions. Look for both absolute and relative risk. If you’re in pharma or biotech: EAIR is no longer optional. The FDA expects it. CDISC requires it for certain trials. Your programming teams need standardized SAS or R scripts. Your medical reviewers need training-35% of them misinterpreted EAIR in early rollout. The industry is changing fast. In 2020, only 12% of FDA submissions included exposure-adjusted metrics. By 2023, that jumped to 47%. By 2027, experts predict 92% of Phase 3 trials will report EAIR alongside traditional rates. This isn’t about statistics for statistics’ sake. It’s about giving patients and doctors the truth-not a simplified number that hides real risk or falsely scares people away from life-saving treatments.What’s Next?

The next wave is automation. Tools like JMP Clinical and R’s survival package are building built-in EAIR calculators. The PhUSE team is releasing a public R implementation in early 2025. The FDA’s draft guidance will likely become final by mid-2025, making EAIR mandatory for many submissions. Until then, the best practice is simple: always ask, “Was exposure time accounted for?” If the answer is no, treat the numbers with caution. If the answer is yes-check the details. How were patient-years calculated? Were interruptions included? Were competing risks modeled? The science of safety is evolving. The old way of counting people who got sick is outdated. The new way-measuring risk over time, accounting for real-life complexity-is the only way to know what a drug truly does to the body.What’s the difference between incidence rate (IR) and exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR)?

Incidence rate (IR) is a simple percentage: number of people who had an adverse event divided by total people in the study. It ignores how long each person was exposed. Exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) divides the total number of events by total patient-years of exposure. This accounts for differences in treatment duration and recurrence, giving a more accurate picture of risk over time.

Why does the FDA now prefer EAIR over traditional incidence rates?

The FDA prefers EAIR because traditional incidence rates can misrepresent risk when treatment durations vary between groups. For example, a drug given for 3 years will naturally have more reported events than one given for 3 months-even if the actual risk per day is the same. EAIR adjusts for exposure time, reducing misleading safety signals and helping regulators make better decisions.

Can I trust a drug’s safety data if it only reports percentages?

Be cautious. If a study only reports percentages without mentioning exposure time, the data may be incomplete or misleading. Especially in long-term trials for chronic conditions, exposure-adjusted metrics like EAIR are essential. Look for phrases like “per 100 patient-years” or “adjusted for duration of treatment.” If they’re missing, the safety profile isn’t fully transparent.

What is a competing risk in clinical trials?

A competing risk is an event that prevents the observation of the adverse event you’re studying. For example, if a patient dies from cancer before experiencing a rare heart side effect, that side effect can’t be observed. Traditional methods treat death as a lost data point, but that inflates the apparent risk of the side effect. Modern methods model competing events separately to give a true estimate.

Is EAIR used in all clinical trials today?

No, but its use is growing rapidly. In 2020, only 12% of FDA submissions included exposure-adjusted metrics. By 2023, that number rose to 47%. For oncology and chronic disease trials, EAIR is now required by CDISC standards. Most major pharmaceutical companies are adopting it, though smaller firms still lag due to complexity and cost.

How do I know if a study properly calculated EAIR?

Look for details on how patient-years were calculated. Proper EAIR uses exact treatment start and end dates, including interruptions or pauses. It should state whether multiple events per person were counted and whether competing risks (like death) were modeled. If the methods section is vague or mentions only “number of patients,” the EAIR calculation may be unreliable.

Donny Airlangga

January 7, 2026 AT 19:05Just read this and had to pause. I’ve been on a med for 4 years and never realized the numbers on the label were this misleading. That 15% headache stat? Could’ve been 2% per year and I’d have no clue. Thanks for laying this out so clearly.

Molly Silvernale

January 8, 2026 AT 00:53Ohhhhh, so it’s not just that people are dumb-it’s that the system is *designed* to make risk look scarier than it is?!! I mean, think about it: if you’re selling a drug, you want people to panic about side effects so you can charge more for the ‘safer’ version… and if you’re a regulator? You want to look like you’re protecting people… so you let the numbers dance. EAIR is the antidote to statistical theater.

And competing risks? That’s not just statistics-that’s life. People die. They don’t get to keep collecting side effects like trading cards. We’ve been pretending death is a glitch in the data when it’s the whole damn plot.

Also-why is no one talking about how this changes the game for chronic illness? If I’m on a drug for 20 years, and I get a migraine every 3 months? That’s 80 events. But if you just count me as ‘one person with migraines’? You’re erasing my reality. EAIR gives me a voice. Finally.

Aubrey Mallory

January 9, 2026 AT 04:57Look, I’ve reviewed 30+ FDA submissions. If your team is still using raw incidence rates in 2025, you’re not just behind-you’re dangerous. EAIR isn’t optional. It’s the floor. And if your SAS scripts are still manually calculating patient-years without tracking treatment interruptions? You’re not doing science-you’re doing guesswork with a fancy spreadsheet.

Stop pretending this is ‘technical.’ It’s about whether someone lives or dies because you misread a number. Get trained. Get the PhUSE macros. Do it now.

christy lianto

January 9, 2026 AT 12:26THIS. I’m a nurse and I’ve had patients cry because a drug label said ‘15% chance of nausea’-but they didn’t know it was over 3 months. When I explained EAIR? They finally felt heard. It’s not just math-it’s trust. And if we keep giving people incomplete numbers, we’re not just misinforming-we’re betraying them.

Also, relative risk is the worst. ‘Doubles your risk!’ sounds like a horror movie. But if your baseline is 0.05%? You’re talking about 1 in 2000. That’s not scary. That’s statistically noise. We need to stop letting marketers hijack science.

swati Thounaojam

January 11, 2026 AT 07:59Manish Kumar

January 12, 2026 AT 10:41Let me tell you something, my friends. This is not merely about statistics-it is about the very epistemology of medical knowledge. The reductionist paradigm of counting bodies, of quantifying suffering into percentages, is a colonial relic of Enlightenment thinking-where the human body becomes a mere dataset, a cipher to be cracked by the priesthood of biostatisticians.

EAIR? It is a postmodern correction, yes-but even it fails to address the ontological violence of medicalization. Why do we assume that every adverse event must be quantified? Why not ask: what does it mean to suffer? To have a migraine for the 17th time in a year? Is that not a narrative? A poem of pain?

And yet-we must use EAIR. Because the system demands it. And in a world where numbers rule, we must speak its language to survive. So yes-use the macros. Calculate the patient-years. But never forget: behind every event is a person who just wanted to feel better.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 12, 2026 AT 21:02Wait, so if someone gets the same side effect 5 times, EAIR counts all 5? That makes sense. But how do you even track that? Do patients remember? Do doctors write it down? Or is this just a fancy spreadsheet that assumes everyone’s perfect at logging their migraines?

Also-what if someone stops the drug for a week, then restarts? Does that break the patient-year? Or do you just add it up? I feel like this is way more complicated than it’s made out to be.

Prakash Sharma

January 13, 2026 AT 18:51USA and EU pushing this EAIR nonsense while India still struggles to get basic meds to villages. You people care more about statistical precision than real people dying from lack of access. Meanwhile, our doctors use ‘percentage’ because it’s all they’ve got. Don’t lecture us on precision when you won’t even fund basic healthcare.

Kristina Felixita

January 15, 2026 AT 15:41OMG I JUST REALIZED WHY MY MOM’S DRUG LABEL SAID ‘15% CHANCE OF HEADACHES’ BUT SHE GOT THEM EVERY WEEK??!! THANK YOU. I’M SHARING THIS WITH EVERYONE. I’M EVEN PRINTING IT OUT FOR HER DOCTOR. SHE’S BEEN SCARED FOR YEARS THINKING IT WAS ‘WORSE’ THAN OTHER DRUGS. NOW SHE KNOWS IT’S JUST TIME. 🥹❤️

Joanna Brancewicz

January 16, 2026 AT 21:25EAIR is the new standard for serious AEs. If your trial doesn’t report it, it’s not fit for regulatory submission. Period. Also, competing risk modeling isn’t ‘advanced’-it’s baseline for oncology now. Stop using KM for non-fatal events.