Idiosyncratic Drug Reactions: Rare, Unpredictable Side Effects Explained

Dec, 15 2025

Dec, 15 2025

Idiosyncratic Drug Reaction Risk Checker

Check Your Medications for Risk

This tool identifies medications with known idiosyncratic drug reaction risks. Most reactions are rare but serious. Always consult your doctor before making any medication changes.

Risk Assessment Results

Symptoms to Watch For

Important: If you experience any of these symptoms while taking medication, stop the drug immediately and contact your doctor.

Most people expect side effects from medications - nausea, dizziness, dry mouth. Those are common, predictable, and often listed on the label. But what if your body reacts to a drug in a way no one saw coming? No one could have predicted it. Not your doctor. Not the clinical trials. Not even the drug makers. That’s an idiosyncratic drug reaction - a rare, unpredictable, and sometimes deadly response that strikes out of nowhere.

What Exactly Is an Idiosyncratic Drug Reaction?

An idiosyncratic drug reaction (IDR) is an adverse reaction that doesn’t follow the usual rules. It’s not caused by taking too much of a drug. It’s not something you can avoid by lowering the dose. It doesn’t happen to most people - only a tiny fraction. The odds? Between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000. That’s like winning a lottery you never entered - and losing badly.

These reactions are called Type B adverse drug reactions, meaning they’re not related to the drug’s main purpose. If a blood pressure pill makes you dizzy, that’s Type A - expected. If that same pill suddenly causes your skin to peel off or your liver to fail, that’s Type B - idiosyncratic.

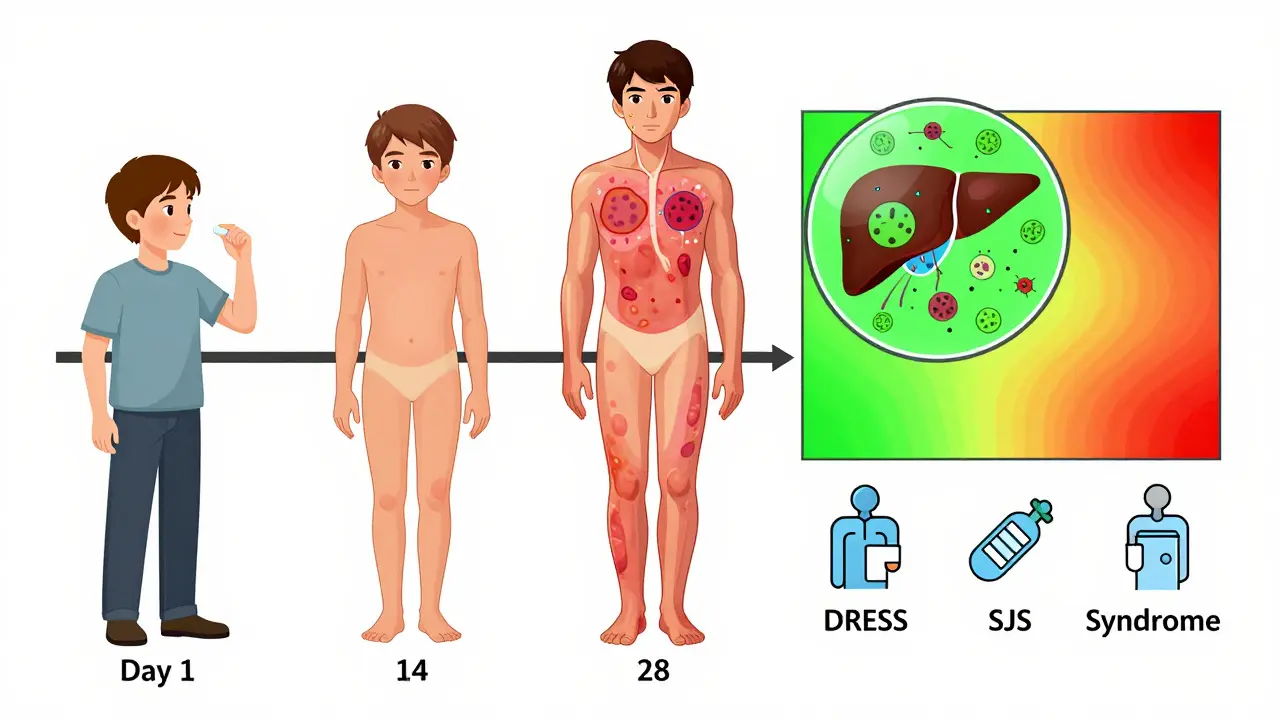

They show up weeks after you start the drug, not hours. You might feel fine for a month, then wake up with a fever, rash, jaundice, or trouble breathing. By then, the damage is already done. And because it’s so rare, doctors often miss it. Patients get told they have the flu, a virus, or even stress - until it’s too late.

Why Do They Happen? It’s Not Just Bad Luck

People used to think these reactions were just bad luck. But science now shows they’re tied to your genes, your immune system, and how your body processes drugs.

One leading theory is the hapten hypothesis. Some drugs break down into reactive chemicals that stick to your body’s proteins. Your immune system sees these altered proteins as invaders - like a virus hiding in plain sight. It attacks. And that’s when things go wrong.

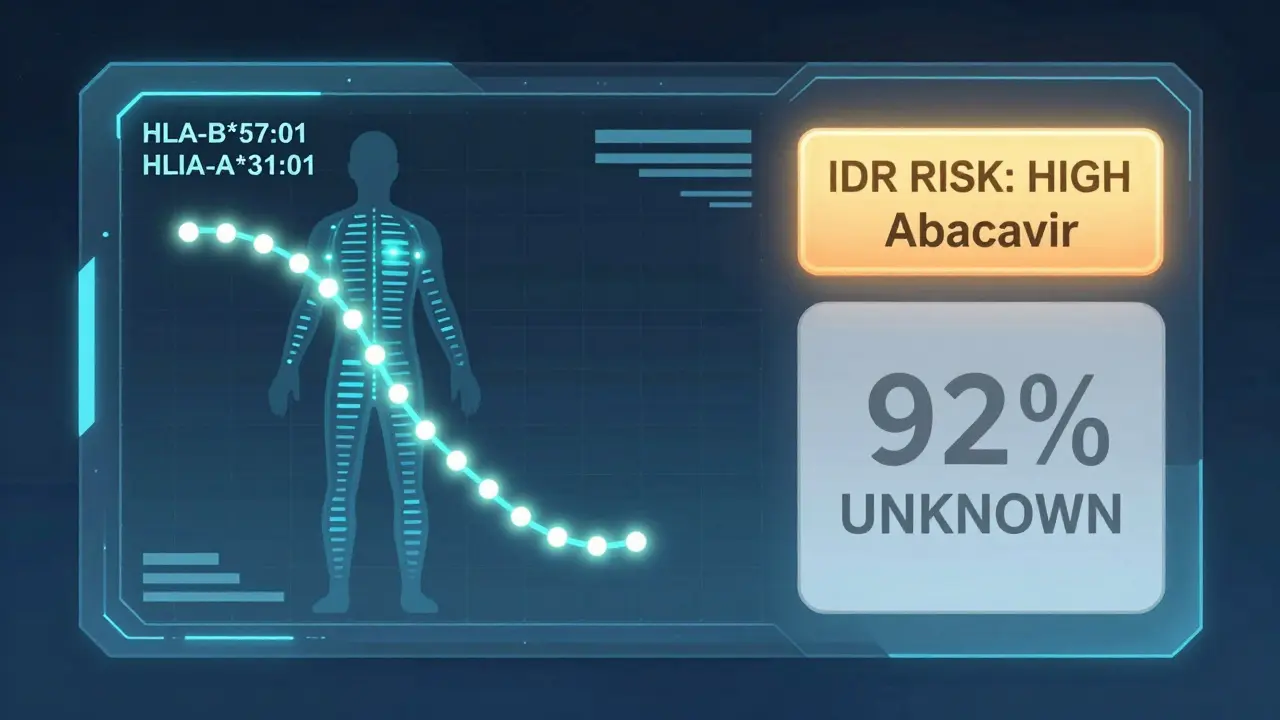

Genetics play a huge role. For example, if you carry the HLA-B*57:01 gene, taking the HIV drug abacavir can trigger a life-threatening allergic reaction. Test for that gene first, and you avoid it entirely. That’s why some hospitals now screen patients before giving certain drugs. But here’s the catch: that’s one of the only cases where we have a reliable genetic test. For 92% of other IDRs, we have no warning signs. No test. No way to know who’s at risk.

Some drugs are more likely to cause these reactions. Antibiotics like sulfonamides, anticonvulsants like carbamazepine, and painkillers like diclofenac are common culprits. But even drugs we think are safe - like statins or antidepressants - can trigger them in rare cases.

The Most Dangerous Types

Not all idiosyncratic reactions are the same. Some are mild. Others are catastrophic. The two biggest threats are:

- Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury (IDILI) - This is the most common. It accounts for nearly half of all serious drug-related liver damage. Symptoms? Yellow skin, dark urine, fatigue, nausea. It can lead to acute liver failure. About 13% of all sudden liver failures in the U.S. are caused by IDIs.

- Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (SCARs) - These include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and DRESS syndrome. Skin blisters, peels, and dies. Mucous membranes swell. Death rates for TEN can hit 35%. DRESS can damage your liver, kidneys, lungs - and come back months later.

These aren’t just side effects. They’re medical emergencies. And they often start slowly. A rash here. A fever there. You think it’s nothing. But within days, it can spiral.

Why Are They So Hard to Spot?

Drug trials involve thousands of people. But even 10,000 participants won’t catch a reaction that hits one in 50,000. That’s why most IDRs aren’t discovered until after the drug hits the market.

And even then, doctors struggle to recognize them. A 2021 study found that 65% of patients with IDRs were initially misdiagnosed. One patient with DRESS syndrome was treated for pneumonia for two weeks - until his skin started sloughing off. Another was told she had hepatitis C - when it was actually her cholesterol drug.

Diagnosis relies on three clues:

- Timing: Symptoms appear 1 to 8 weeks after starting the drug.

- Severity: The reaction is way worse than the drug’s known effects.

- No other cause: No infection, no autoimmune disease, no other drug explains it.

Doctors use tools like RUCAM for liver injury and ALDEN for skin reactions. But these aren’t perfect. They’re tools for suspicion - not confirmation.

What Happens When It’s Too Late?

Once an IDR happens, the first rule is simple: stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions.

But stopping the drug doesn’t always fix things. Liver damage can be permanent. Skin damage can leave scars. Some patients develop chronic conditions - autoimmune hepatitis, lung fibrosis, kidney problems - years after the reaction.

There’s no antidote. No magic pill. Treatment is mostly supportive: steroids to calm the immune system, IV fluids, liver support, intensive care. For DRESS or TEN, patients often need burn unit care. The mortality rate for severe cases? Up to 35%.

Re-exposure - giving the drug again to confirm the diagnosis - is rarely done. It’s too risky. One patient in 100 might die. So doctors rely on dechallenge: if symptoms fade after stopping the drug, it’s likely the culprit.

Patients Speak: The Hidden Toll

Behind the statistics are real people.

A woman in Ohio took a common painkiller for back pain. Three weeks later, her skin blistered. She spent 18 days in the hospital. Her insurance denied coverage for follow-up care. She lost her job. She still gets rashes when she’s stressed.

A man in Florida was on an antiviral for hepatitis C. He developed DRESS. His liver failed. He needed a transplant. His story? He was told he had the flu. Twice.

A 2022 survey of 687 patients found 72% had delayed diagnoses. 61% felt dismissed by their doctors. The average out-of-pocket cost for a severe IDR? $47,500. Many never fully recover.

But there’s hope. Specialized clinics - like the Mayo Clinic’s Drug Safety Clinic - cut diagnosis time from 14 days to under 5. How? They know what to look for. They act fast.

What’s Being Done to Prevent Them?

The pharmaceutical industry is losing billions because of IDRs. Drugs get pulled from the market. Lawsuits follow. Companies now screen for reactive metabolites in early development. Pfizer, for example, won’t move forward with a drug if its toxic metabolites exceed 50 picomoles per milligram of protein.

Regulators are stepping up. The FDA now requires detailed metabolite testing for drugs with high systemic exposure. The EMA requires immune monitoring for new cancer drugs. In 2023, the FDA approved the first predictive test for pazopanib - a kidney cancer drug - that can identify patients at risk for liver injury with 82% accuracy.

Genetic research is accelerating. Scientists have found 17 new gene-drug links since 2022. One of them? HLA-A*31:01 and phenytoin - a seizure drug. Now, in some countries, doctors test for that gene before prescribing phenytoin.

Projects like the NIH’s $47.5 million Drug-Induced Injury Network and the EU’s ADRomics initiative aim to combine genetics, immune profiling, and AI to predict reactions before they happen. The goal? Reduce severe IDRs by 60-70% in the next decade.

But here’s the truth: we’ll never eliminate them. The human immune system is too complex. Too personal. Too unpredictable.

What You Can Do

You can’t predict an IDR. But you can protect yourself.

- Know your meds. If you’re prescribed a new drug, ask: “Has this caused serious reactions in others?” Look up the drug on LiverTox or the FDA’s database.

- Track symptoms. Write down when you started the drug and what you feel each day. Fever? Rash? Nausea? Yellow eyes? Don’t wait.

- Speak up. If something feels wrong, say it. Don’t let a doctor brush you off. Say: “I started this drug three weeks ago, and now I have X. Could this be related?”

- Know your family history. If someone in your family had a bad reaction to a drug, tell your doctor. It might matter.

- Ask about testing. If you’re prescribed abacavir, carbamazepine, or allopurinol - ask if you should be tested for HLA genes. It’s simple. It could save your life.

Most people will never have an IDR. But if you do, early recognition is everything. The difference between diagnosis in 3 days versus 3 weeks? It’s the difference between recovery and death.

Final Thought

Idiosyncratic reactions remind us that medicine isn’t just science - it’s biology. And biology is messy. Drugs work differently in every body. What’s safe for one person can be deadly for another. We’re getting better at spotting these reactions. But until we can predict them with certainty, vigilance is your best defense. Pay attention. Ask questions. Don’t assume it’s just a side effect. Sometimes, it’s something far more dangerous - and far more personal.

What causes idiosyncratic drug reactions?

Idiosyncratic drug reactions are caused by complex interactions between a drug’s chemical properties and a person’s unique biology - especially their immune system and genes. The most accepted theory is the hapten hypothesis, where a drug breaks down into reactive molecules that bind to body proteins, tricking the immune system into attacking its own tissues. Genetic factors, like certain HLA gene variants, play a major role in who develops these reactions.

How common are idiosyncratic drug reactions?

They’re rare, affecting between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000 patients. But despite their low frequency, they’re responsible for 30-40% of all drug withdrawals from the market because they’re often severe, unpredictable, and deadly. They make up about 13-15% of all adverse drug reactions overall.

Can you test for idiosyncratic drug reactions before taking a drug?

Only for a few specific drugs. For example, testing for the HLA-B*57:01 gene before taking abacavir (an HIV drug) prevents life-threatening reactions in nearly all cases. Testing for HLA-B*15:02 before carbamazepine reduces risk of severe skin reactions in Southeast Asian populations. For over 90% of drugs, no reliable pre-use test exists.

What are the most dangerous types of idiosyncratic reactions?

The most dangerous are idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (IDILI), which can cause acute liver failure, and severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) like Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and DRESS syndrome. These can be fatal - with death rates up to 35% for TEN - and often require intensive care or organ transplants.

How long after starting a drug do idiosyncratic reactions appear?

They typically appear 1 to 8 weeks after starting the drug. This delayed onset is one reason they’re so hard to diagnose - symptoms don’t show up right away, and doctors often don’t connect them to the medication until the reaction is advanced.

Can you get an idiosyncratic reaction from a drug you took before without problems?

Yes. Idiosyncratic reactions can happen even if you’ve taken the drug before without issue. The immune system can become sensitized over time. A reaction may occur on the second, third, or even tenth exposure - with no prior warning.

What should you do if you suspect an idiosyncratic reaction?

Stop the drug immediately and seek medical attention. Do not wait for symptoms to get worse. Tell your doctor exactly when you started the medication and describe all symptoms - even mild ones like fatigue or low-grade fever. Early recognition can prevent life-threatening complications.

Are idiosyncratic reactions the reason some drugs get pulled from the market?

Yes. Between 1950 and 2023, 38 drugs were withdrawn from the U.S. market primarily because of idiosyncratic toxicity - including troglitazone (for liver failure) and bromfenac (for liver injury). These reactions are the leading cause of post-marketing drug withdrawals, far more than predictable side effects.

Is there any way to prevent idiosyncratic drug reactions?

Prevention is limited but improving. For a few drugs, genetic testing can prevent reactions. Drug companies now screen for reactive metabolites during development. Regulators require better safety testing. But the best prevention for patients is awareness: know your meds, track symptoms, and speak up if something feels wrong.

What’s the future of predicting idiosyncratic reactions?

The future lies in combining genomics, immune profiling, and artificial intelligence. Projects like the FDA’s IDR Biomarker Qualification Program and the EU’s ADRomics initiative aim to identify patterns that predict risk before a drug is even prescribed. Experts believe we can reduce severe IDRs by 60-70% in the next decade - but we’ll never eliminate them completely due to the complexity of human biology.

Anu radha

December 15, 2025 AT 17:26Meghan O'Shaughnessy

December 16, 2025 AT 07:16Kaylee Esdale

December 16, 2025 AT 23:47Brooks Beveridge

December 17, 2025 AT 10:04Jane Wei

December 18, 2025 AT 08:06Jonathan Morris

December 20, 2025 AT 01:00Erik J

December 20, 2025 AT 17:07BETH VON KAUFFMANN

December 21, 2025 AT 16:04Patrick A. Ck. Trip

December 21, 2025 AT 17:50Sam Clark

December 21, 2025 AT 18:31Virginia Seitz

December 22, 2025 AT 01:44amanda s

December 22, 2025 AT 17:48