How to Report a Suspected Adverse Drug Reaction to the FDA

Dec, 16 2025

Dec, 16 2025

Every year, millions of people take prescription and over-the-counter drugs without issue. But for some, a medication causes harm-sometimes serious, sometimes life-threatening. If you’ve experienced an unexpected side effect, or if you’re a healthcare provider who’s seen one, reporting it to the FDA isn’t just helpful-it’s critical. The system exists to catch dangers that clinical trials missed. And guess what? You can be the one to start that process.

Why Reporting Matters

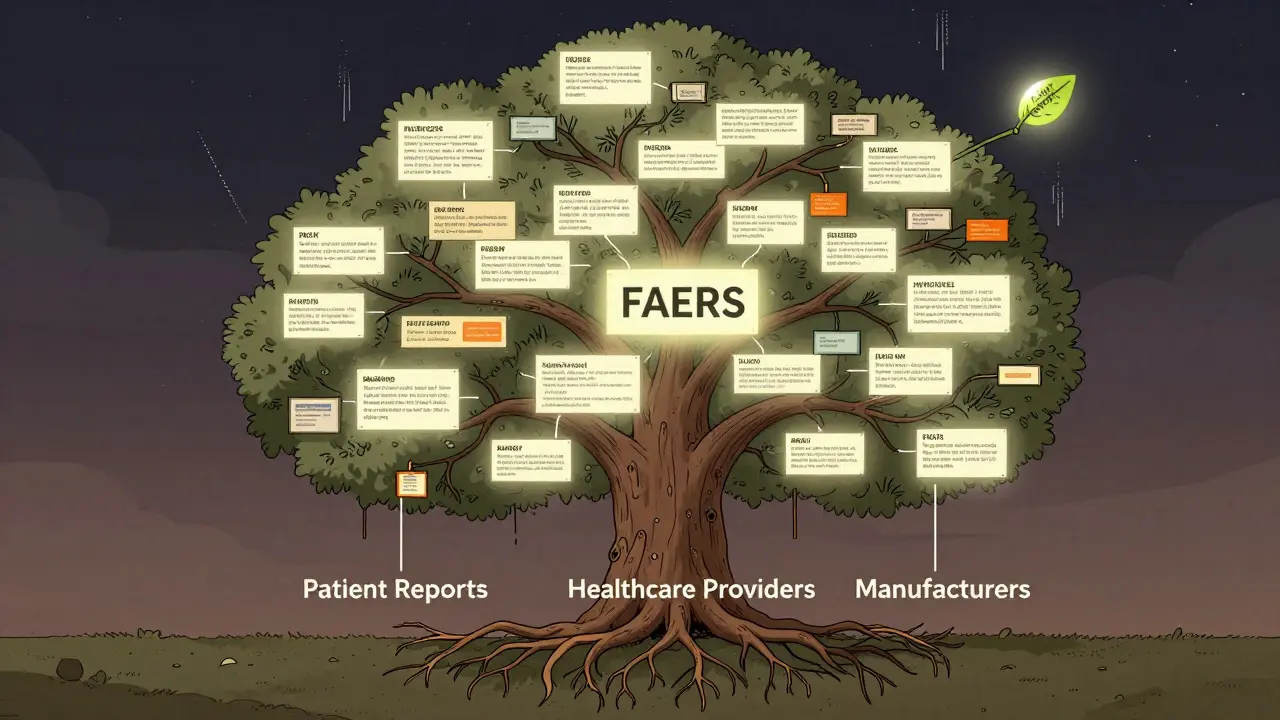

Clinical trials test drugs on a few thousand people. That’s not enough to catch rare side effects. Once a drug hits the market, millions use it. That’s when hidden risks show up. The FDA’s FAERS (the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) collects these reports to spot patterns. A single report might seem small. But when dozens or hundreds come in about the same drug and same reaction, the FDA investigates. That’s how dangerous drugs get black box warnings, or even pulled from the market.Here’s the hard truth: only about 6% of serious adverse reactions get reported. Most people don’t know how-or think it’s not their job. But if you’re the one who noticed it, you’re the most important person in the chain. Your report could save someone else’s life.

What Counts as a Reportable Reaction?

Not every weird feeling counts. The FDA defines a serious adverse event (an unexpected, harmful reaction to a drug that meets specific criteria) as one that:- Causes death

- Is life-threatening

- Leads to hospitalization or extends an existing hospital stay

- Results in permanent disability or damage

- Causes a birth defect

- Requires medical intervention to prevent permanent harm

Even if you’re not sure the drug caused it, report it anyway. The FDA doesn’t need proof-just a reasonable suspicion. For example, if you started a new blood pressure medication and three days later had a stroke, that’s reportable. If you took a new painkiller and developed a rash that didn’t go away, that’s reportable. If your child had a seizure after taking a new antibiotic, report it.

Who Can Report?

Anyone can report. That includes:- Patients and family members

- Doctors, nurses, pharmacists

- Caregivers and long-term care staff

Manufacturers are legally required to report serious reactions within 15 days. But you don’t need to wait for them. Your report matters just as much.

How to Report: Three Simple Ways

There are three ways to submit a report. All are free and confidential.1. Online via MedWatch (Fastest and Recommended)

Go to www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch. Click “Report a Problem.” You’ll fill out Form 3500 (the FDA’s official adverse event reporting form). It asks for:- Patient info: age, sex, weight (no name or address needed)

- Drug details: brand name, generic name, dose, how often taken, start and stop dates

- Reaction details: what happened, when it started, how long it lasted, how bad it was

- Outcome: did the person recover? Were they hospitalized?

- Your info: name, phone, email (optional but helpful for follow-up)

It takes about 20 minutes. You can save your progress and finish later. Once submitted, you’ll get a confirmation number. The FDA receives over 1.8 million reports a year-40% of them come through MedWatch.

2. By Phone

Call the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information Hotline at 1-800-FDA-1088. A representative will take your report over the phone. This is good if you’re not comfortable typing or need help understanding what to say. The average wait time is under 10 minutes. They’ll mail you Form 3500 to sign and return if needed.3. By Mail

Download Form 3500 from the MedWatch site, print it, fill it out, and mail it to:FDA MedWatch

5600 Fishers Lane

Rockville, MD 20857

This takes longer, but it’s still valid. Use this if you don’t have internet access.

What Happens After You Report?

Your report goes into the FAERS (the FDA’s safety database). It’s anonymized and combined with thousands of others. Analysts look for patterns. If 10 people report the same rare liver injury after taking Drug X, the FDA may:- Ask the manufacturer to update the warning label

- Issue a safety alert to doctors and pharmacies

- Launch a formal investigation

One real example: a nurse reported severe low blood sugar in patients using a new diabetes drug. Within 47 days, the FDA updated the label to warn about this risk. That happened because someone spoke up.

Common Mistakes People Make

Even with good intentions, people mess up. Here’s what to avoid:- Waiting to be sure. You don’t need proof. If you think it might be the drug, report it.

- Leaving out the drug name. If you don’t know the generic name, write the brand name. Even if you’re not sure which drug caused it, list all recent meds.

- Skipping the timeline. When did you start the drug? When did the reaction start? This helps determine if it’s linked.

- Thinking it’s not serious enough. A rash that lasts weeks? A dizzy spell that causes falls? Those count.

What If You’re a Healthcare Provider?

If you’re a doctor, nurse, or pharmacist, you’re on the front lines. You see these reactions regularly. But 63% of providers say they don’t report because they’re too busy. Don’t let that be you.Here’s a quick checklist:

- Identify the drug and reaction.

- Confirm it’s serious (use the list above).

- Fill out Form 3500-online in under 30 minutes.

- Copy your patient’s chart and keep a record.

- Report even if the patient’s insurance or hospital says it’s not required.

Some hospitals have internal reporting systems. That’s good. But it doesn’t replace reporting to the FDA. Only the FDA sees all reports nationwide. That’s how patterns emerge.

What’s New in 2025?

The system is getting smarter. By December 2025, electronic health records will be required to send adverse event alerts directly to the FDA. That means fewer missed reports. Also, the FDA is starting to monitor social media for mentions of drug side effects-so if someone posts about a bad reaction online, the FDA might reach out to them. Your report still matters more.The FAERS Public Dashboard 2.0 (a real-time public tool to view safety data) is now live. You can search it yourself. See what reactions are being reported for your medication. Knowledge is power.

Still Unsure? Call for Help

If you’re stuck, call the FDA’s MedWatch hotline at 1-800-FDA-1088. They have pharmacists and nurses on standby to help you fill out the form. No judgment. No pressure. Just help.Or email [email protected]. They reply within 24 hours. They’ve helped thousands of people just like you.

Final Thought: Your Voice Has Power

You don’t need to be a scientist or a doctor to make a difference. You just need to notice something wrong-and speak up. Every report adds to the data. Every report helps the FDA protect others. And if your report leads to a warning label, a safer dose, or even a drug recall? That’s not just a win. That’s justice.Do I need to give my name when reporting an adverse drug reaction to the FDA?

No, you don’t have to give your name. The FDA accepts anonymous reports. But if you include your contact information, they can follow up if they need more details. That helps them understand your report better and may lead to faster action. Your information is kept confidential and is never made public.

Can I report a reaction to an over-the-counter (OTC) drug or supplement?

Yes. The FDA’s MedWatch system covers prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, herbal supplements, and even cosmetics. If you had a bad reaction to a popular pain reliever, a weight-loss pill, or a new probiotic, report it. Supplements aren’t tested like drugs, so your report is especially valuable.

How long does it take for the FDA to act after a report is filed?

There’s no fixed timeline. The FDA reviews every report, but action depends on how many similar reports come in. One report won’t trigger a recall. But if 50 people report the same serious reaction to the same drug within a few months, the FDA will investigate. That’s how they spot patterns. It can take weeks or months, but your report is stored and counted.

What if I report and nothing changes? Was it a waste of time?

No. Every report adds to the data. Many drug safety changes happen because of dozens or hundreds of individual reports. Even if you don’t see a label change or recall, your report may have helped a future patient avoid harm. The system works cumulatively. You’re part of a network that protects public health.

Can I report a reaction for someone else, like a child or elderly parent?

Absolutely. Family members, caregivers, and guardians are encouraged to report on behalf of others. Just provide the patient’s age, sex, and medical details. You don’t need legal permission. The FDA understands that vulnerable people often can’t report for themselves.

Are there penalties for not reporting an adverse reaction?

Consumers and patients face no penalties for not reporting. But manufacturers and healthcare providers are legally required to report serious reactions. If they fail to do so, they can face fines or enforcement actions. For patients, the only penalty is missing a chance to help others.

Is the MedWatch website easy to use on mobile?

The MedWatch portal works on mobile browsers, but it’s not optimized for small screens. Many users rate the mobile experience low-around 4.2 out of 10. For the best experience, use a laptop or desktop. If you’re on the go, call 1-800-FDA-1088 instead. A live agent can guide you through the report over the phone.

What if I don’t know the exact name of the drug I took?

If you don’t know the name, describe it as best you can: color, shape, markings, how often you took it, what it was for. If you have the bottle or packaging, take a photo. The FDA can often identify the drug from a description. Don’t skip reporting just because you’re unsure of the name.

Joe Bartlett

December 17, 2025 AT 19:18Just reported my wife’s rash after that new ibuprofen-took 12 minutes online. FDA doesn’t need your name, just the facts. Simple. Do it.

Naomi Lopez

December 18, 2025 AT 20:52It’s staggering how many people still think adverse reactions are ‘just bad luck.’ The FDA’s FAERS system is one of the few public health mechanisms that actually empowers laypeople to act as sentinel surveillance. Your anecdote, properly documented, becomes data-and data drives policy. If you’re not reporting, you’re complicit in systemic underdetection.

Marie Mee

December 19, 2025 AT 15:46They’re tracking us through our meds now… I bet this is how they build the vaccine database for the next phase… I saw a guy on TikTok say the FDA uses this to link people to their phones… I’m not reporting anything anymore. Too creepy. They already know what I take.

Salome Perez

December 20, 2025 AT 21:40As someone who has worked in global health policy for over two decades, I cannot overstate the profound importance of public participation in pharmacovigilance. The MedWatch system, though under-resourced and underutilized, remains one of the most elegant examples of civic science in action. Your willingness to document-even if you’re uncertain-creates a mosaic of evidence that protects vulnerable populations worldwide. Thank you for being part of this quiet, vital infrastructure.

Martin Spedding

December 22, 2025 AT 04:42lol the FDA gets 1.8M reports a year and 98% are junk. My aunt reported a headache after eating a banana. This system is a joke. Waste of time.

Raven C

December 23, 2025 AT 23:45...I just... I can't believe people treat this like a formality... I mean, think about it-someone’s child could be hospitalized because a report was ignored... and you just... shrug... and say, 'it’s probably nothing'... it’s not just negligence-it’s moral failure... I’m crying right now... I’ve seen it... I’ve seen the charts... the names... the dates... the silence...

Donna Packard

December 25, 2025 AT 18:26I reported my dad’s reaction to his blood thinner last month. Didn’t know if it mattered-but I did it. Just wanted to say: thank you for writing this. It gave me the push I needed.

Patrick A. Ck. Trip

December 26, 2025 AT 11:11Thank you for this comprehensive and meticulously structured overview. While the MedWatch portal’s mobile interface remains suboptimal, the underlying principle-democratizing pharmacovigilance-is profoundly aligned with public health ethics. I have personally submitted three reports as a clinician, and while institutional reporting systems exist, they do not substitute for direct federal reporting. Your clarification regarding supplements and anonymous submissions is especially valuable. I encourage all colleagues to embed this practice into routine care protocols.