Biologic Patent Protection: When Biosimilars Can Enter the U.S. Market

Dec, 4 2025

Dec, 4 2025

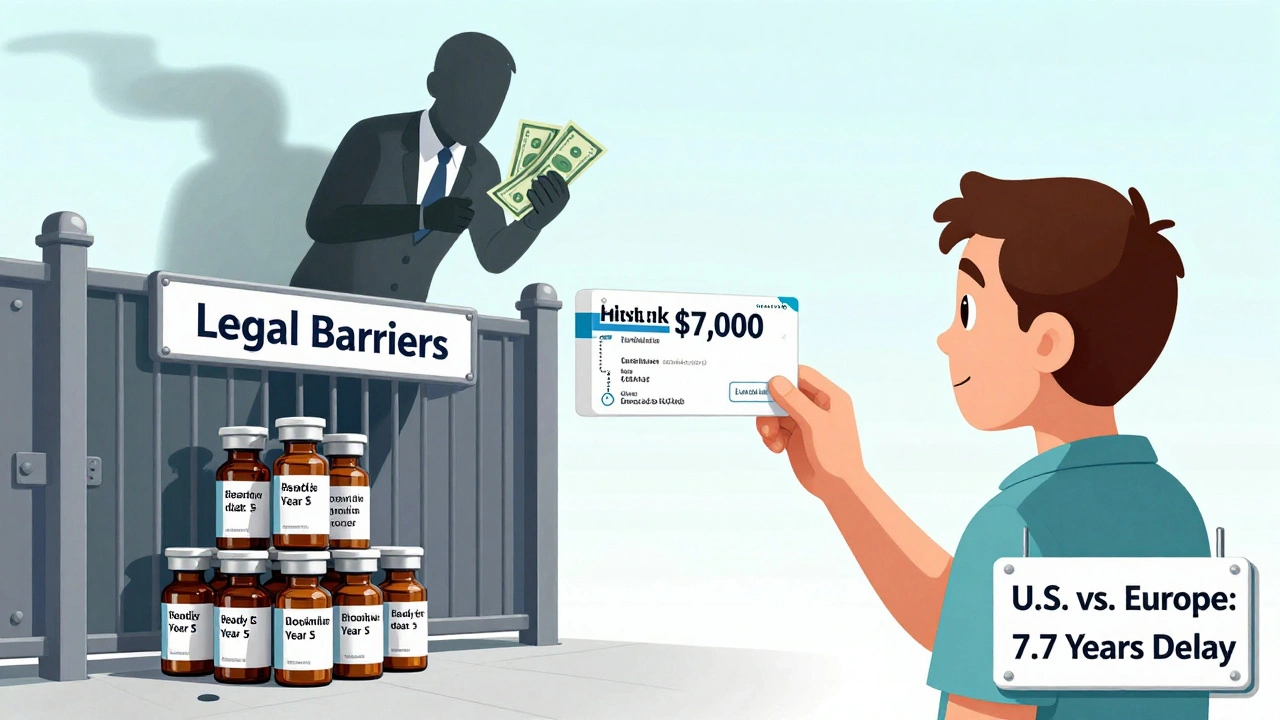

When a biologic drug hits the market, it doesn’t just cost a lot-it comes with a legal shield that can block cheaper versions for over a decade. Unlike generic pills, which can copy a small-molecule drug as soon as its patent expires, biosimilars face a maze of patents, exclusivity rules, and lawsuits before they can even be approved. In the U.S., the clock doesn’t start ticking on biosimilar competition until 12 years after the original biologic gets FDA approval. That’s not a patent expiration date-it’s a government-mandated monopoly. And it’s why Americans pay up to three times more for the same drugs than patients in Europe.

What Exactly Is a Biologic, and Why Does It Matter?

Biologics are medicines made from living cells-usually proteins, antibodies, or gene therapies. They’re not chemically synthesized like aspirin or metformin. Think Humira, Enbrel, or Keytruda. These drugs treat rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. Because they’re made in living systems, they’re incredibly complex. No two batches are exactly alike. That’s why you can’t just copy them like a generic pill. You have to prove you can make a version that’s highly similar with no clinically meaningful differences in safety or effectiveness. That’s what the FDA calls a biosimilar. The problem? Even if you nail the science, you still have to fight through a legal system designed to delay your entry.The 12-Year Exclusivity Rule: How the Law Blocks Competition

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), passed in 2010, created the rules for biosimilars. It’s not just about patents-it’s about two layers of protection. First, there’s a 4-year data exclusivity period. During those four years, no biosimilar company can even submit an application to the FDA. Not a single page of data. Nothing. Then comes the 8-year approval exclusivity. Even if a biosimilar applicant files right after year four, the FDA can’t approve it until 12 years after the original drug launched. That’s 12 years of zero competition. And if the original drug maker gets a pediatric extension-which many do-the clock can stretch to 12.5 years. Compare that to the EU: 10 years of data exclusivity, then 1 year of market exclusivity-11 total. Japan: 8 years data, 4 years market-also 12. But the U.S. is the only country that combines both exclusivity periods so rigidly. The result? The average biologic in the U.S. faces biosimilar competition 7.7 years later than in Europe. For Humira, that meant U.S. patients paid full price until 2023, while Europeans had cheaper versions since 2018.The Patent Dance: A Legal Trap for Biosimilar Makers

The BPCIA includes something called the “patent dance.” It sounds like a friendly negotiation. It’s not. Here’s how it works: Once a biosimilar company submits its application, it must hand over its entire manufacturing plan to the original drug maker. The original company then has 60 days to list every patent they think might be violated-sometimes over 100. The biosimilar maker responds with legal arguments on why each patent doesn’t apply. Then both sides enter a 15-day negotiation to pick which patents to fight over. Most of the time, the original company files lawsuits on dozens of patents at once. These lawsuits can drag on for years. AbbVie, the maker of Humira, held over 160 patents on a single drug, many of them filed years after the original patent expired. Courts often side with the big pharma companies, and biosimilar makers are forced to delay launch while they fight legal battles they can barely afford. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled in Amgen v. Sandoz that skipping the patent dance was allowed-but most biosimilar companies still play along, hoping to avoid even more lawsuits. It’s a lose-lose.

Why So Few Biosimilars Are in Development

You’d think with so many biologics set to lose exclusivity by 2034, biosimilar makers would be rushing in. But they’re not. A 2023 report found that 118 biologics will lose protection between 2025 and 2034-worth $234 billion. But only 12 of them have biosimilars in development. Why? - **High cost**: Developing a biosimilar takes 5 to 9 years and costs over $100 million. Generic pills? $1-2 million and two years. - **Complex drugs**: Antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and cell therapies are even harder to copy. None have biosimilars in the pipeline yet, even though 16 will lose patent protection by 2034. - **Orphan drugs**: 64% of expiring biologics treat rare diseases. Fewer patients mean less profit. Only one orphan biologic, eculizumab, has a biosimilar in development. - **Low sales potential**: Some biologics are used by so few people that it’s not worth the investment. The result? A “biosimilar void.” Many of the most expensive drugs will stay monopoly-priced for years after their patents expire, simply because no one can-or will-make a copy.Who Pays the Price?

It’s not just insurers. It’s patients. A 2023 Arthritis Foundation study found Humira’s list price in the U.S. jumped 470% between 2012 and 2022. In Europe, where biosimilars entered early, prices stayed flat. Patients in the U.S. are skipping doses, splitting pills, or quitting treatment altogether because they can’t afford it. A National Community Pharmacists Association survey found 63% of pharmacists have patients who abandoned biologic therapy due to cost. Dr. Peter Bach of Memorial Sloan Kettering says U.S. cancer patients pay 300% more than Europeans for the same drugs. That’s not a pricing difference-it’s a policy failure.

What’s Being Done? Not Enough

The FDA released a Biosimilars Action Plan in 2022 to improve communication and speed up approvals. But progress is slow. Since 2015, the U.S. has approved 38 biosimilars. Europe has approved 88. Legislation like the Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022 tried to reduce regulatory delays-but it died in committee. Without real policy changes, the system stays broken. The Congressional Budget Office estimates biosimilars could save the U.S. $158 billion over the next decade-if we fix the barriers. Under current rules? Just $71 billion.What’s Next?

The next wave of expiring biologics includes drugs for multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and severe asthma. If nothing changes, patients will keep paying inflated prices while companies fight over patents. The science to make biosimilars exists. The demand is there. What’s missing is the political will to cut through the legal and economic barriers that protect profits over patients. Until then, the 12-year clock keeps ticking-and Americans keep paying the price.Can a biosimilar be approved before the 12-year exclusivity period ends?

No. Under U.S. law, the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar until 12 years after the original biologic’s approval date. Even if a biosimilar application is submitted after year four, the agency must wait until year 12 to grant approval. This is a statutory exclusivity period, not a patent issue-it’s enforced regardless of whether patents are still active.

Why are biosimilars more expensive to develop than generic drugs?

Biosimilars are made from living cells, not chemicals. Their structure is far more complex, and tiny changes in manufacturing can affect safety or effectiveness. Developers must run extensive analytical tests, animal studies, pharmacokinetic trials, and sometimes clinical trials to prove similarity. Generic drugs, by contrast, are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs and require far less testing. Biosimilar development costs $100 million or more; generics cost $1-2 million.

Do patents expire before the 12-year exclusivity period ends?

Yes, often. Many biologics have core patents that expire well before the 12-year mark. But companies file dozens-sometimes hundreds-of secondary patents on formulations, delivery methods, or uses. These patent thickets, like AbbVie’s 166 patents on Humira, are used to extend market control beyond the original patent. The 12-year exclusivity period overrides these expiring patents, ensuring no biosimilar can enter even if the core patent is gone.

How does the U.S. compare to other countries on biosimilar access?

The U.S. has the longest exclusivity period at 12 years. The EU offers 10 years of data exclusivity plus 1 year of market exclusivity (11 total). Japan and South Korea also offer 12 years, but with different structures. The U.S. also has the most aggressive use of patent litigation to delay entry. As a result, biosimilars enter markets in Europe and Japan years earlier than in the U.S., leading to significantly lower drug prices.

Are there any biosimilars already on the market in the U.S.?

Yes. Since 2015, the FDA has approved 38 biosimilars for use in the U.S., including versions of Humira, Enbrel, Neulasta, and Avastin. But many of these launched only after long legal delays. For example, the first Humira biosimilar didn’t enter until 2023, 13 years after the drug’s approval. Market uptake remains slow due to payer restrictions and lack of provider education.

sean whitfield

December 6, 2025 AT 11:12aditya dixit

December 6, 2025 AT 20:56Norene Fulwiler

December 8, 2025 AT 06:46William Chin

December 9, 2025 AT 12:07Lucy Kavanagh

December 10, 2025 AT 10:44Chris Brown

December 11, 2025 AT 11:28Stephanie Fiero

December 12, 2025 AT 07:04Laura Saye

December 14, 2025 AT 06:04Michael Dioso

December 14, 2025 AT 08:15Krishan Patel

December 14, 2025 AT 13:00Ada Maklagina

December 14, 2025 AT 18:36James Moore

December 15, 2025 AT 07:54Kylee Gregory

December 15, 2025 AT 15:30Stephanie Bodde

December 17, 2025 AT 08:20Philip Kristy Wijaya

December 17, 2025 AT 20:53